Guy Fawkes Night 2018

Guy Fawkes – a summary

Guy Fawkes was born in York around 13 April 1570. Although there is some uncertainty surrounding the exact date of his birth, church archives confirm that he was baptised on 16th April 1570 at the church of St Michael le Belfrey. His parents Edward and Edith Fawkes were Protestant, and as such, it is believed that Guy was raised in the Protestant faith.

When he was eight years old, the young Fawkes attended St Peter’s School in York. It was here that he first made the acquaintance of two brothers, Jack and Christopher Wright, who would become his comrades in the plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament some thirty years later.

Catholic conversion

Guy’s father died in 1579 when Guy was just nine-years-old and within two years his mother had remarried a Catholic man called Denis Bainbridge. Many believe that Guy’s conversion to the Catholic faith was due to his stepfather’s influence. It is unclear exactly when Fawkes adopted Catholicism, but it is widely accepted that he was a confirmed and devoted Catholic by the time he turned 21.

The year 1591 proved to be a momentous one for Fawkes. As soon as he came of age, he sold the property he had inherited from his father and made preparations to leave England for the Continent. An active and passionate man of striking appearance, Fawkes wasted no time in signing up to the Spanish Army of Flanders. He was to spend the next 12 years as a mercenary soldier in the Low Countries, fighting with Catholic forces against Protestant resistance. It was during this time that Fawkes, who had earned the reputation of a good-living, loyal and brave soldier, gained a thorough knowledge of gunpowder – and it was this expertise which was to ultimately lead to his downfall.

The willing recruit

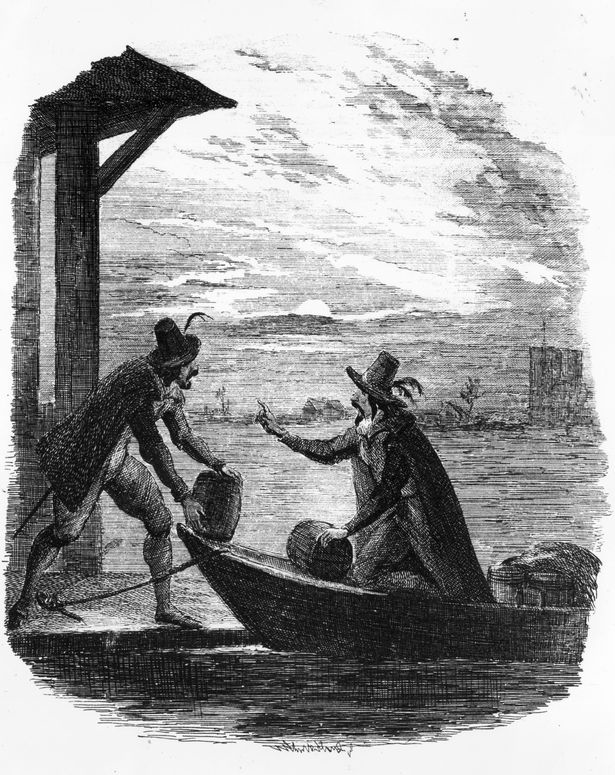

It may surprise many to learn that Guy Fawkes, despite his name being synonymous with the Gunpowder Plot, was not the main architect of the conspiracy. The scheme was proposed by a group of Catholic cousins in England, two of whom were Guy’s old school-friends, the Wright brothers. The leader of this tight-knit group of conspirators set about recruiting Fawkes on the strength of his reputation as a courageous soldier, his loyalty to his Catholic faith and, of course, his gunpowder expertise. Fawkes, who had by then adopted the name Guido, proved to be a willing recruit; he landed in England in April 1604, ready to take up the Catholic cause.

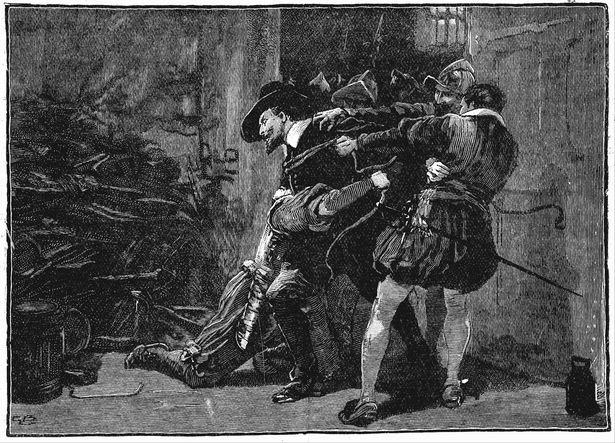

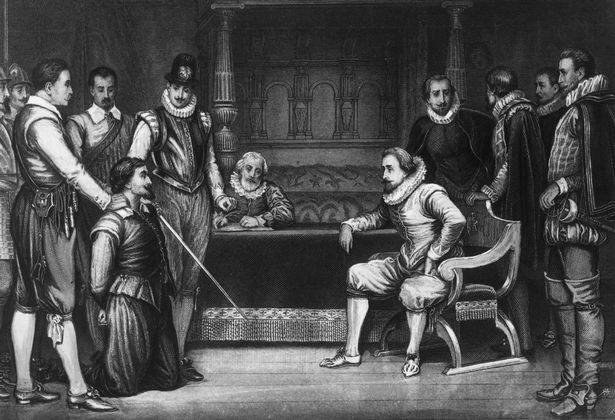

And so began Guido Fawkes’s involvement with the doomed plot to blow up King James I, Lords and Commons on November 5th, 1605. The scheme was foiled, and Guido was caught red-handed, on the night of 4th November, in a vault under the Palace of Westminster. This vault contained 36 barrels of gunpowder, enough to blow the Houses of Parliament sky-high. He was arrested, imprisoned in the Tower of London and tortured. He succumbed on the night of 7th November and confessed all to his inquisitors. His fate was sealed.

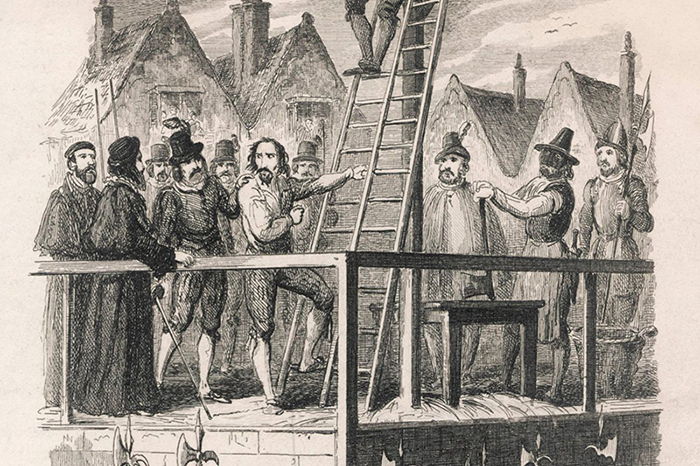

A traitor’s death

Fawkes’s trial took place on 27th January 1606. He was found guilty of treason and sentenced to death by the grotesque means of hanging, drawing and quartering (this gruesome sentence was common for those convicted of betraying King and country). However, Fawkes’s execution, which took place on 31st January, was mercifully swift; the hangman’s noose broke his neck and he was thus spared the agony of a traitor’s death.

Every year on 5th November, as bonfires blazed throughout the Kingdom to commemorate the King’s deliverance from the terrorist plot, the legend of Guy Fawkes became inextricably linked with the story of the Gunpowder Plot, to the extent that 5th November has become known as ‘Guy Fawkes Night’. His legend continues unabated to this day.

Bonfire night

Guy Fawkes Night, also known as Bonfire Night or Firework Night, is an annual commemoration observed on 5th November, primarily in Great Britain. Celebrating the fact that King James I had survived the attempt on his life, people lit bonfires around London, and months later the introduction of the Observance of 5th November Act enforced an annual public day of thanksgiving for the plot’s failure.

Within a few decades Gunpowder Treason Day, as it was known, became the predominant English state commemoration, but as it carried strong Protestant religious overtones it also became a focus for anti-Catholic sentiment. Puritans delivered sermons regarding the perceived dangers of popery, while during increasingly raucous celebrations common folk burnt effigies of popular hate-figures, such as the pope. Towards the end of the 18th century reports appear of children begging for money with effigies of Guy Fawkes and 5th November gradually became known as Guy Fawkes Day. Towns such as Lewes and Guildford were in the 19th century scenes of increasingly violent class-based confrontations, fostering traditions those towns celebrate still, albeit peaceably. In the 1850s changing attitudes resulted in the toning down of much of the day’s anti-Catholic rhetoric, and the Observance of 5th November Act was repealed in 1859. Eventually the violence was dealt with, and by the 20th century Guy Fawkes Day had become an enjoyable social commemoration, although lacking much of its original focus. The present-day Guy Fawkes Night is usually celebrated at large organised events, centred on a bonfire and extravagant firework displays.